In my first post in this three-part series on the biomedical system, I discussed the fundamental flaw in using ‘the best’ indiscriminately, without acknowledging that, more often than not, there is no universal, Platonic ideal. In this post, I’m going to explore how choosing our ranking system requires a deeper conversation about where it is that we, as a scientific community, want to be in twenty or thirty years.[1]

In some ways, choosing between scientists is a lot like judging the Westminster dog show. Essentially, judges have to find a way to compare apples and oranges. And then rank the huge diversity. At Westminster, the judges have to say that this Siberian husky [2] is better than that beagle; at the NIH, they have to say that this scientist should be funded while that one should not be.

This is a hard problem. Really hard.

So how could we rank scientists to decide on ‘the best’? Well, there are few approaches. One class of approaches is to consider only the scientist, and judge him/her by one of several metrics,[3] such as:

- Productivity;

- Efficiency (e.g. average cost per publication);

- Scientific significance;

- Technological innovation;

- Commitment to teaching;

- Creativity;

- Risk-taking;

- Experience;

- Reputation.

To me, though, this straightforward approach misses the most important [4] difference between a dog show and the NIH: while Westminster chooses one winner, the NIH chooses to fund many scientists. That is, the NIH funds a portfolio, and so it must consider the strength of an individual scientist in relation to the other scientists.

You would be completely justified in stammering right about now, Doesn’t this approach just make things even more complicated?

Well, yes and no.

Yes: Now there are a lot of moving parts:

- How many scientists should be focused on training graduate students?

- How important is efficiency in respect to productivity?

- How important is a diverse (in all senses of the word) community of scientists?

- What is the right balance between foundational science and translational research?

- What is the right mixture of high-risk/high-reward and low-risk/low-reward projects?

And no, because now we can think about how the funding decisions are shaping the scientific community. Not just the scientific community of today, but also the scientific community of the future.

It’s true, this aspect puts a lot of pressure on us. However, this very fact—that our funding decisions today affect future science—also gives us a toehold into the very tricky problem of ranking apples and oranges.

The easiest way to untangle this issue is to take a step back and flip our perspective around. Rather than decide on the specific metrics for the portfolio and then watch how that affects the community over the next decade, we should instead use an approach of deciding where we want to be, as a community, in twenty, thirty years and base our metrics upon that destination. That goal, that vision, that ideal is our North Star.

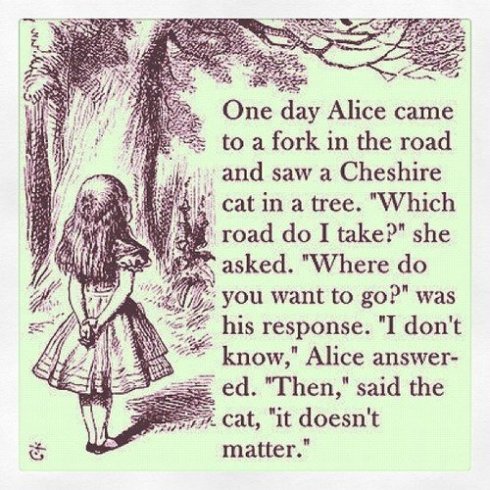

After all, if you don’t know where you’re going, how can Google maps decide on the best route? And if you don’t know where you’re going, how will you know when you’ve arrived? And how on earth will you ever know if you’re off course?

I don’t presume to have the perfect answer, but I’ll put out my utopian scientific community anyway, one that I hope we can move towards during my career as a scientist. Here, we would:

- Be diverse (gender, racially, geographically, area of interest);[5]

- Embrace the power of technological innovation;

- Encourage risk-taking;

- Support interdisciplinary interactions that often drive discoveries;

- Evaluate projects while keeping a long horizon in mind;

- Value scientific quality and rigor more than immediate scientific impact;

- Consider scientific efficiency, rather than just productivity;

- Understand the give-and-take relationship between foundational and translational (i.e. applied) research;

- Reverse the trend of the ever-increasing length of apprenticeship;

- Promote real scientific literacy in the public.

This, of course, is just one answer to the overarching question of ‘where do we want to go?’ I have no doubt that other scientists (and the general public and politicians) will give different answers.

But let’s have the conversation.

Let’s recognize that until we tackle this question, talking about ‘the best scientist’ is virtually meaningless. Let’s admit that we are doing our own sort of evolution experiment each time we fund some scientists, and not others. Let’s acknowledge that the community and the colleagues and the scientists of the next decade are the ones that will best flourish in the environment we set today.

Scientists, I think it’s time that we had an honest discussion about where we want to go. And then we can decide how to get there.

[1] I should be upfront here: I don’t have all (or any) of the answers. More specifically, I don’t know how, in this era of harsh, Draconian funding lines, to choose between all of the extraordinary science that is going on. I don’t know how to deal with the fact that, even if we had a perfect set of judging criteria, many scientists who should be funded are not going to be. And I really don’t know how to make that okay.

[2] I’m really much more a cat, than dog, person. But I do have a pretty big soft spot for Siberian huskies.

[3] At this point, let’s not even worry about how to actually measure these traits.

[4] Well, I guess, that the contestants at Westminster are dogs and scientists are human is a pretty important difference too. Details, details.

[5] Studies have shown that diverse workplaces are more productive. But, for me, the argument in support of diversity is a moral one of basic fairness.

The dog show analogy is perfect, but I’m not so sure the Alice thing is fair. Plenty of funded researchers (I try not to lump the sciences together, and I especially try to keep engineers in a separate category), plenty of them have more backbone than Alice in Wonderland. And they pay a price for it.

I have a small issue here. With the recent focus on citation counts, and the ability to normalize for co-authors in the “citation core” (i.e., for true colleagues as opposed to students included for charitable or mentoring reasons), and do all sorts of other kinds of analysis, we have so much better measures of productivity and impact than ever before. Why would this be the time to pull back on metrics? I agree wholeheartedly that it is time to think about the divisors, so that we look at efficiency, not just output. For most big researchers, if you divide by total grad students and funding (with some appropriate mixture), you get a different picture. ALl of these numbers paint a much better picture than we have ever had.

Of course, the h-index is probably not appropriate for people in my field, but the bibliometrics people have a lot of ideas now, such as the h(i)(30,bias)-f(age), which correlates well with reputation (normalize by real co-authors, divide by 30, do the h-thing, adjust for field bias, and subtract a small function of number of years active), according to some study at MIT. I prefer other metrics, but the point is that this is a lot better than counting publications, or counting total funding, which were the only things that mattered for most of my early career. Unfortunately.

I actually have a bigger issue with the “let’s figure out where we want to go, first” recommendation. It’s a great idea when you want to get to the moon, map the human genome, find all the terrorists, or beat the Germans to the H-bomb. But I don’t think normal science benefits from a lot of centralized direction. At least not on short time horizons. I’ve always liked the Canadian model precisely because it admits that there are a lot of paths, a lot of smart people doing interesting things, and a lot of folly in assuming that one bureaucracy, or two or even three, can figure out reliably who deserves the awards. Now, some science is big and requires competition for the big pot. Frankly, I’ve heard some of my physics friends out their own colleagues as b-o-g-u-s when it comes to their constant super-collider super-funding requests. But some times some one has to get the big contract, and there is not enough tax revenue for two. The U.S. funding agencies do seem to be very good at making that decision.

So I would just like to see some combination of the big money competition, which we do well, and the broad subsistence, let-many-flowers-bloom, spread-it-around approach of the Canadians. Why can’t we have both? Ha ha, maybe the response to the Cheshire cat is the Schroedinger one.

You raise two good points here. The first being how should we measure even something as “simple” as productivity? I’m not an expert on this, but I agree with you: it should be something much more nuanced than simply papers per unit time. I’m not convinced that we have the right formula for this (nor am I entirely convinced that counting publications encourages scientists the right way), but I think we’re doing a better job than we used to.

As for the second point. It’s the classic bottom up/top down conundrum! I think you’re right here too: we need a mix of both.

In a sense, one of my favorite models for this balance is Google. Clearly there is a top-down direction that provides not only overarching goals but also a culture for doing things “the Google way.” But what also seems to work very well for them is that they also encourage bottom-up initiatives by giving workers space/time to pursue their own ideas. (Drive by Daniel Pink has a great discussion on why work environments like this do so well with innovation and productivity. For instance: this sort of free research time is how post-it notes were developed at 3M!)

Still, there is something to be said for deciding from the outset, in a broad sense, on what sort of scientific culture we want–what sort of science we value, etc.–and this is what I was thinking of in my post. After all, saying that there is a lot about Google to emulate is already saying quite a lot about the culture we like!